WORCESTER — For Dominique Muldoon, the strike at Saint Vincent Hospital has never been about the money.

“For a registered nurse, not being able to do our jobs properly really puts people’s lives on the line,” said Muldoon, a 19-year veteran of Saint Vincent Hospital who also co-chairs the local bargaining unit of the Massachusetts Nursing Association.

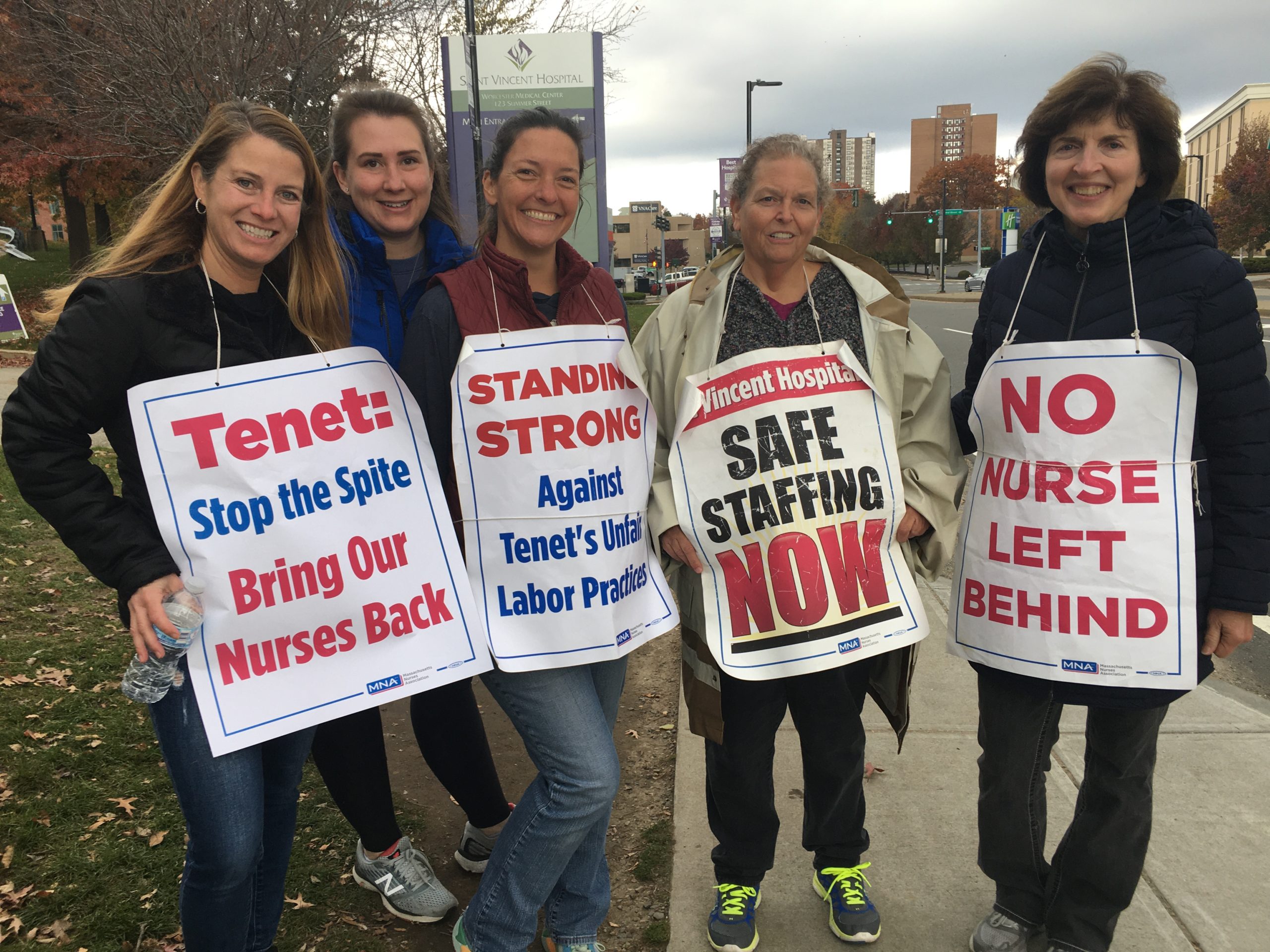

Muldoon is one of several hundred nurses who went on strike on March 8, citing concerns over staffing shortages and increasingly dangerous conditions brought on by the coronavirus pandemic.

“We didn’t have the proper isolation gown to protect us or our families,” said Muldoon. “We had airbags that were donated from Ford Motor Company; these large gowns that were made out of airbags that were supposed to be washable, but we’d get them out of the laundry and they would smell mildewy.”

Now into its eighth month, the Saint Vincent nurses’ strike is said to be one the longest nurses strikes in Massachusetts history.

Muldoon says part of the reason the strike has dragged on for so long is because of the job-related discrimination women face in the workforce, which includes a lack of negotiation from the hospital, highly punitive measures and a willingness to replace nurses with specialties and decades of experience with recent graduates.

“We are a female dominated industry, we do have men – very competent nurses in our field – but at least 90 percent of us are women and it seems to be that there’s some sexism. I have never seen this happen with a male dominated union,” she said. “And some of the rhetoric from the hospital, if we don’t accept their last offer, they are going to do this to us or do that to us – it’s been all about that the whole strike, they wouldn’t negotiate with us the first couple of months.”

On Oct. 15, hospital administrators issued their “last, best and final offer in negotiations with the MNA for a new contract,” according to a statement on the hospital’s website.

Back in August, Saint Vincent hired over 100 “permanent replacement nurses” who took over for some of the nurses on strike. It was also around this time that hospital administrators made an offer to the nurses’ union, stating that they would increase nurse staffing, improve workplace safety measures, reduce out-of-pocket healthcare expenses and give 35 percent raises to some nurses. Initially, the union agreed to the deal, but balked when they found out that some of the returning nurses would not be able to return to their prior – often specialized – positions.

“It doesn’t make any sense to honor people that have held these jobs for months over people who have helped them for years. I have been here for 16 years,” said Sandra Thomas, a cardiac stepdown nurse who was on strike outside the hospital on Nov. 10. “I don’t know if my 32-hour day position is still available, but 16 years is a hell of a lot longer than a couple months.”

Thomas said that the hospital has put recent grads in highly specialized positions, undermining the experience of some of those who held the positions before.

“[They put] new grads in specialty positions, those are the positions that they filled. They filled the same day surgery positions, GI lab positions, some maternity and Center for Women and Infant positions,” she said.

She added that placing new grads in these highly specialized roles was comparable to interchangeably hiring specialized doctors, for instance, hiring a nephrologist to do the work of a cardiologist.

“By definition it’s an economic strike, they don’t have to honor positions, but I think what makes the most sense is just give the experienced and educated and vested people, give them back their jobs,” said Thomas.

Matthew Clyburn, the communications manager of Saint Vincent Hospital, was “astonished” when he heard what Muldoon and Thomas had to say.

“These just seem to me like wild allegations. I mean, how do you disprove a negative?” he said.

Clyburn went on to disagree with Thomas, stating that the experience level of those who accepted permanent replacement positions were mixed.

“Over 75 percent of the nurses who accepted permanent replacement positions have at least six years of experience and 25 percent have over 20 years of experience,” said Clyburn. Later adding, “The allegation that they have been replaced by less qualified staff is just completely untrue.”

He added that many of those who took the replacement nursing positions were members of the MNA and that Tenet Healthcare, the for-profit healthcare company based in Texas that owns Saint Vincent Hospital, has been negotiating consistently with the nurses for years.

“We have had federally mediated negotiation going back for more than a year,” said Clyburn. “Negotiations have been ongoing, discussions have been ongoing, we have had countless negotiating and bargaining sessions with men and women in the room.”

David Schildmeier, the Director of Public Communications at the MNA, said that it’s irrelevant how much prior experience the permanent replacement nurses have because no nurse should be replaced.

“Even if you bought their numbers, we don’t believe anything that Tenet says, it’s still of concern. Here’s the bottom line, no nurse should be replaced; it’s unconscionable,” said Schildmeier.

Schildmeier added that Tenet was required by law to send information about who was hired into the permanent replacement positions, stating that a nurse with 40 years’ experience in the level two nursery (who was also on the MNA’s committee) was replaced with a nurse who had less than a year of experience. Another nurse in that same unit with 35 years’ experience, was replaced with a “nurse with little experience.”

“There might be a lot of nurses with six years’ experience or more, they are replacing nurses with 20, 30, 40 years’ experience,” he said. “Whether or not they have six years’ experience, replacing a nurse who has been there for 20 years, taking care of the same patients every day, day in day out, who knows the physicians, knows the equipment, knows the systems in place, there is no way you can make those equivalents.”

Leave A Comment